4 Command Line Basics

In this session will introduce the command line as a general concept and learn a few commands that are complimentary to git.

4.1 Overview

- Teaching: 30 min

- Exercises: 15 min

4.1.1 Questions

- What is the shell, command line, or terminal?

- Why do I need to know the command line to use git?

- How do I use the command line?

- What commands do I need to know?

4.1.2 Objectives

- Understand for to form file paths and navigate directories

- Understand how arguments and flags are used to modify command line commands.

- Understand the concept of wild cards ’*’.

4.2 Introduction

git is fundamentally a command line tool. Although there are many graphical user interfaces that can simplify its use, none contain the full set of features available on the command line.

If you ever encounter trouble with a git repository, or need to find out how to do something important with it, you will invariably stumble across help in the form of command line instructions. This is why comfort with the command line is essential for learning git.

4.3 Shell, command line, cli, terminal

All these words in the title above are used interchangeably to mean the same thing: a sparse window, usually with a dark backgroud and light text, featuring a prompt followed by a cursor. In the movies hacking computers often involves people typing really fast into this window.

The command line interface (cli), is a text-based interface to a computer program. Pretty much everyone primarily uses a Graphical User Interface (GUI) to interact with their programs, but historically this is only recent. Most of the time we’ve had with computers has been using text-based interfaces and often the GUI can only access a subset of functionality available on the cli. There are many important programs that only have a cli (e.g. pandoc).

‘Terminal’ is short for ‘terminal emulator’ which is to say it is a program which emulates a physical input and display device called a terminal, that used to connect to a mainframe computer in the early days of computing. It is the program that draws the dark background, light text, and cursor.

A ‘shell’ is a program that provides a cli to your operating system. Think of the functionality your operating system provides: manipulating your file system, running and stopping programs, changing system settings etc. All of this can be done via text with a shell. When you ‘open a terminal’ the program that the terminal is talking to initially is a shell. For a given operating system you often have a choice of many shells. The most popular shell is the ‘Bourne Again Shell’ or ‘bash’.

4.5 Manipulating the Filesystem

The shell provides commands to create, move, and delete folders and files.

4.5.1 Creating Folders

Let’ create an example project folder from the command line:

First we’ll use the mkdir command to make a directory. The argument to

the command is the path of the directory to be created. To create a

directory in the current folder we just need to use its name since and the path

is assumed to be relative.

miles@miles-macbook:~$ mkdir eg_projectConfirm the project folder exists using ls and change into it with cd:

miles@miles-macbook:~$ ls

miles@miles-macbook:~$ cd eg_projectThen we’ll create several more folders as if the project is an analysis, mkdir

can create multiple directories at once, for each argument passed.

mkdir doc data results scripts4.5.2 Moving Folders/Files

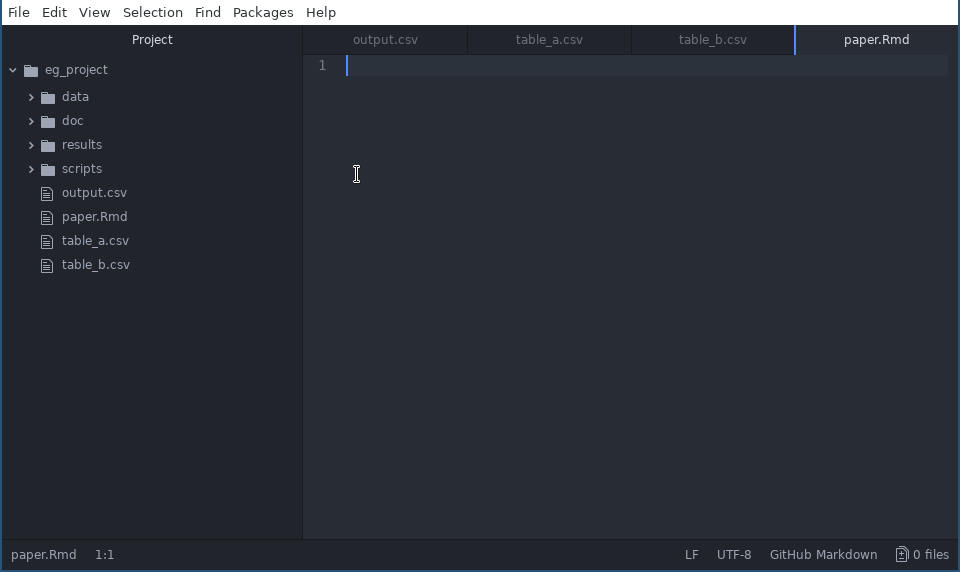

Using Atom we’ll create some empty files. To open our project use File -> Open Folder… and select the ‘eg_project’ folder.

Create the 4 files in the eg_project folder as shown:

They don’t need to contain anything.

Let’s say we want to move the .Rmd file to the scripts folder. We can use the mv command to move files or folders. mv takes two arguments, the first being files or folders to move and

the second being the path to move then to. Our command would look like:

miles@pa00120549:~/eg_project$ mv paper.rmd scriptsLet’s say we don’t like the name ‘scripts’ since ‘paper.Rmd’ is not really a

script - it’s a source file. We can also use mv to rename files and folders, by

moving them to a new place in the file system e.g.:

miles@pa00120549:~/eg_project$ mv scripts src4.5.2.1 Move a file

Move ‘output.csv’ into the results folder of ‘eg_project’ using the mv command.

4.5.2.2 Rename a file

Complete the command below to rename the ‘paper.Rmd’ file to ‘methods.Rmd’ using mv:

miles@pa00120549:~/eg_project$ mv src/paper.Rmd ...Be sure to check your result using ls.

4.5.3 Wildcards and Manipulations

Now we’re going to see how we can use wildcards to perform actions on many

files or folders at once. A wildcard is the the * symbol, and it can be used to provide file system arguments that match patterns.

For example, lets say we want to list all the data files in the current folder:

miles@pa00120549:~/eg_project$ ls -alh *csvThis lists all files that end in ‘csv’. We could also use it a the end of a path to match all items that start with a prefix, e.g. also folders starting with ‘d’:

miles@pa00120549:~/eg_project$ ls -alh d*We can use this with all types of file manipulations!

4.5.3.1 Move a group

- Using a single

mvcommand, move the csv files with ‘table’ in the name to the ‘data’ folder.

4.5.4 File Removal

The rm command can be used to remove files and folders. It takes the path of

the files or folders as its argument. It requires the -r (recursive) flag

to remove folders.

To remove the ‘doc’ folder we’d do:

miles@pa00120549:~/eg_project$ rm -r doc4.5.4.1 Wildcard extermination

- Combine the

rmcommand with two wildcards to remove all .csv files in our project with a single command.

Hint: You can use a wildcard in the path for both the folder and file name portion.

4.6 Summary

In this lesson we’ve:

- Demystified some of the jargon associated with the command line.

- Learned the anatomy of cli commands: paths, arguments, and flags.

- Learned about relative and absolute paths, including useful short hands (

~,..,.) - Seen wildcards in action.

- Learned a handful of shell commands.

This is but a tiny fraction of what is available using the shell. The main objective here was to communicate some ideas that come in handy with git. You might like to see: http://swcarpentry.github.io/shell-novice/ for a more complete introduction.`